Taken on it's own "A Girl Walks Home Alone at Night" is a very striking title. It conjures up real world horror of being a woman and existing after the sun is down. However, the film belies any notion of investigation into those very words and the complex dangers of being a woman. Instead of delving deep into feminist text or analyzing the horror of violence against women it brandishes itself as vampiric cinema, and tends to have more in common with conventional boy meets girl romance despite it's interest in terror. If anything this is closer to quirky cinema, and wouldn't make a bad double feature with Jim Jarmusch's Only Lovers Left Alive considering both films follow similar narrative structures, but A Girl Walks Home Alone at Night feels like the first chapters of a budding relationship between two loners instead of the stagnant problems of eternal life.

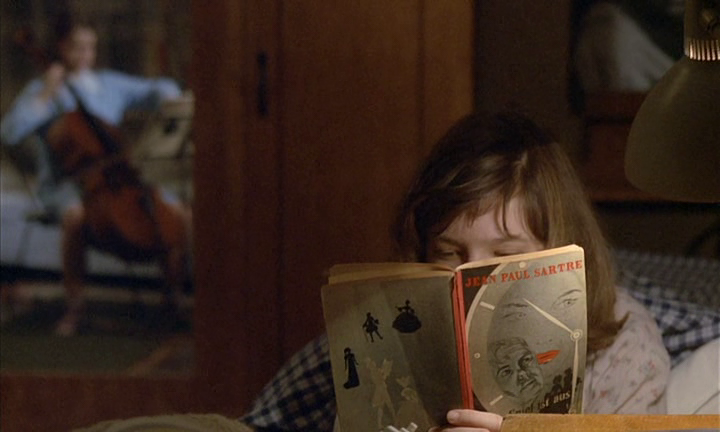

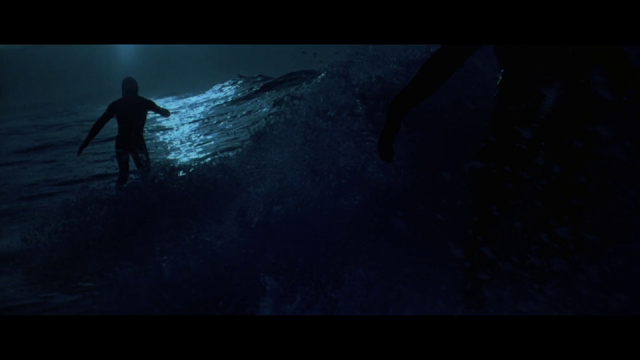

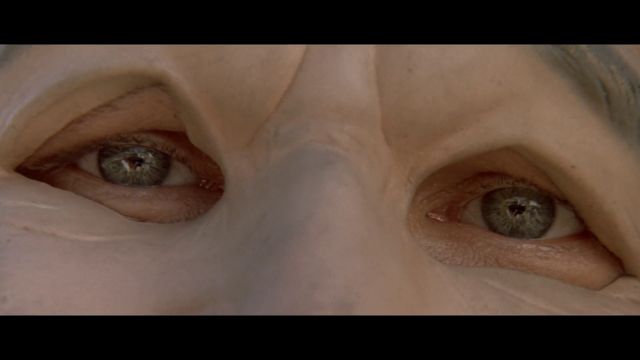

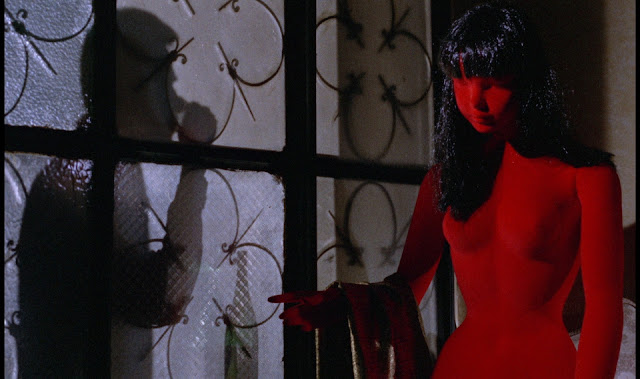

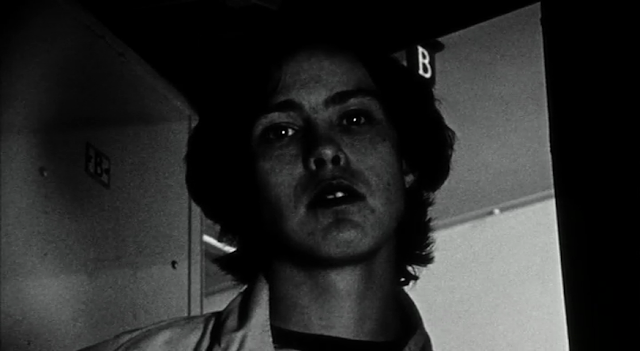

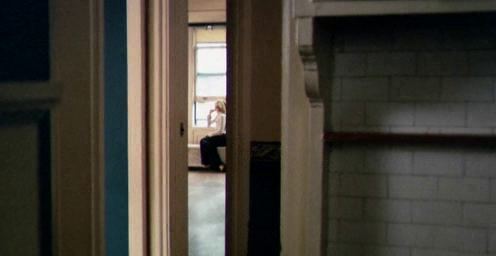

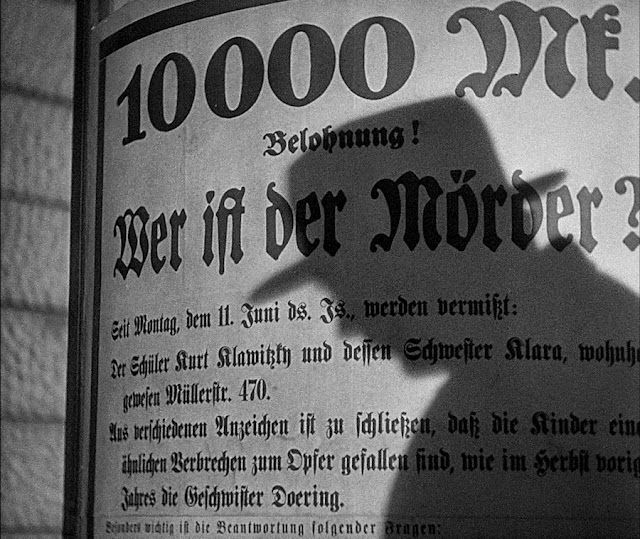

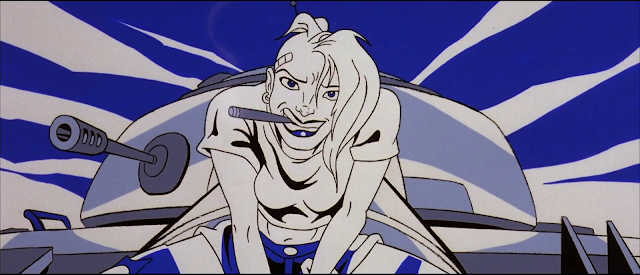

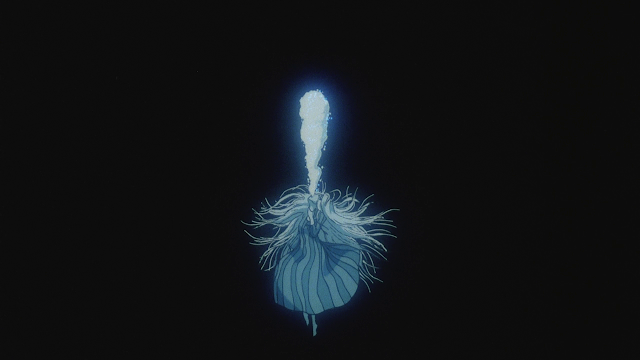

The first thing one would notice about this movie is the stylization of the image. Night time cinematography gives way to dusty digital black and white in what has to be one of the first usages of B&W digital to grand effect. Lights feel hazey and street lamps decorate streets row upon row as far as the eye can see creating a sense of almost suburban trappings meets the old west. Amirpour's intentions of making the picture feel like a western aren't lost on her sensibilities to reach back to cinema of the past to give weight to some of her ideas. The urban streets traveled by no one except a cloaked girl aren't entirely separate from wanderers of the old west like Clint Eastwood in High Plains Drifter. The old drunk trope is replaced by an elderly relative stricken by grief and hooked on heroin. These are tropes certainly, but Amirpour works well within them, and her knowledge of cinema past increases the effectiveness of her concrete wasteland. Aside from those western locales there is an intense interest in interior design with each room signifying the attitudes of specific characters. Her first victim lives a chic lifestyle that is coded by tacky animal print everywhere. The Vampire lives in a basement with paintings of Madonna on her wall, and the rest of her room seems to be corroding around her. The insertion of character dynamics via interior design and cinematography that doesn't feel watery like other BW Digital work (Frances Ha) are some of the more impressive feats here.

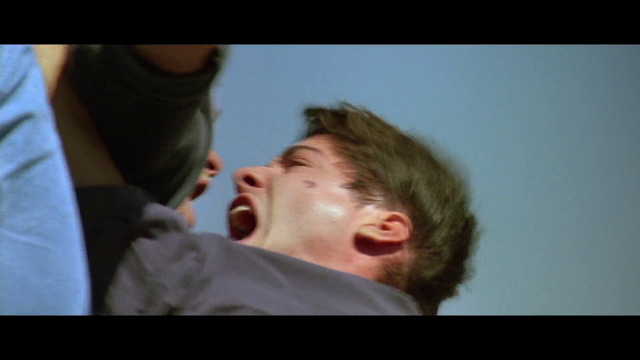

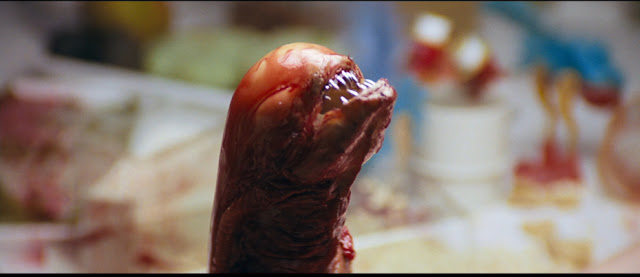

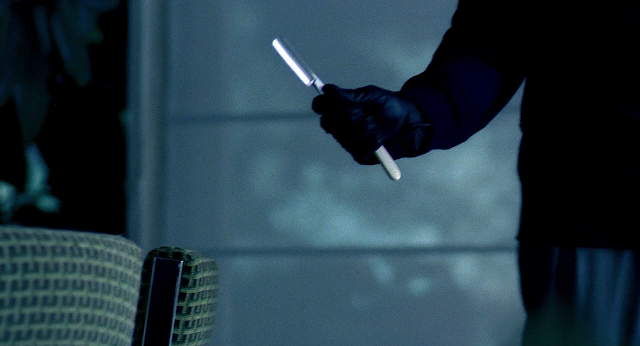

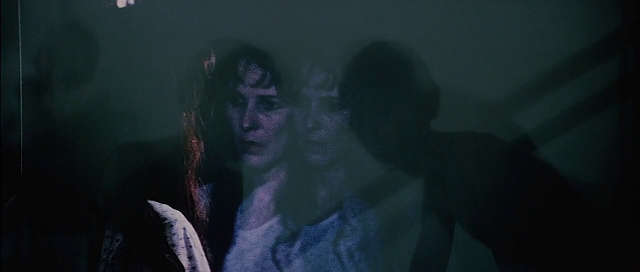

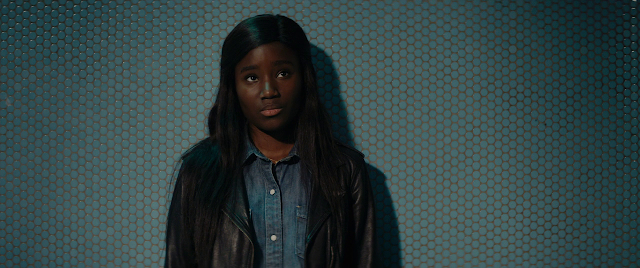

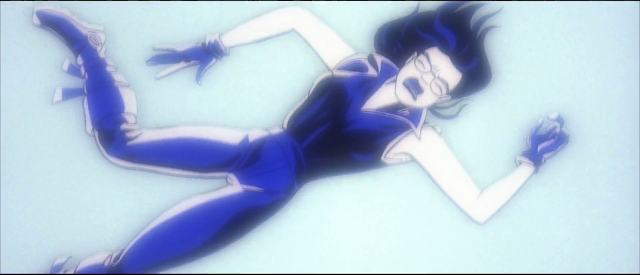

Scenes of violence tend to forgo the western and dip back into horror, and occasionally feminist horror. The black and white of Abel Ferrara's The Addiction is handled with much more chaotic-frenzied-brutality than this picture, but The Addiction came to mind specifically in feeding sequences while I was watching this. Lily Taylor's vampire intellectual and Shelia Vand's vampire, misandrist, queen both have no predisposition towards softness, and their killings often revel in the sensuality of the feast. Vand's vampire specifically only attacks men, and I think that codes this with some feminist text, even though the picture refuses to analyze these things much deeper than her only killing males (though the way she does kill the first man in this picture is reminiscent of Teeth). It can be read that she is cleansing the streets, but that's only the case until she falls for a boy dressed as dracula.

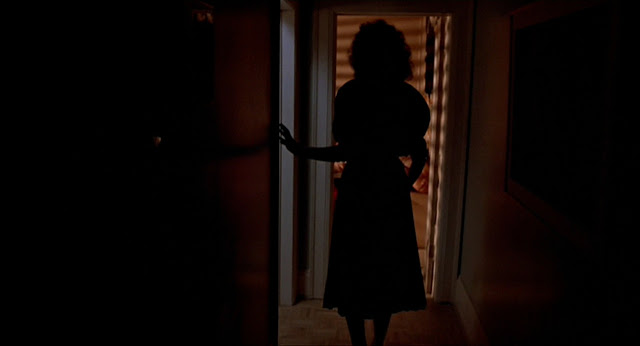

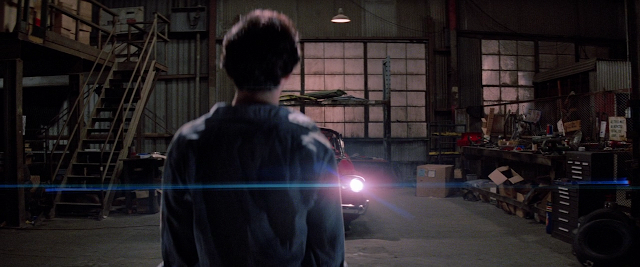

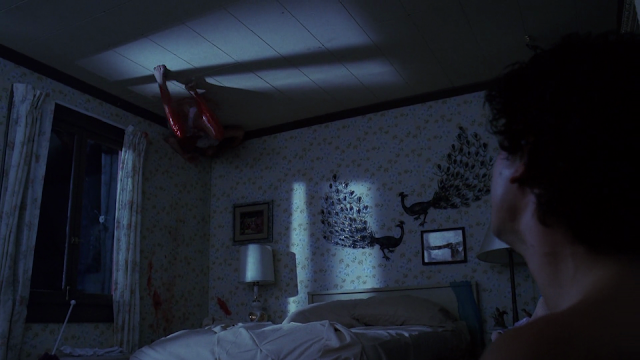

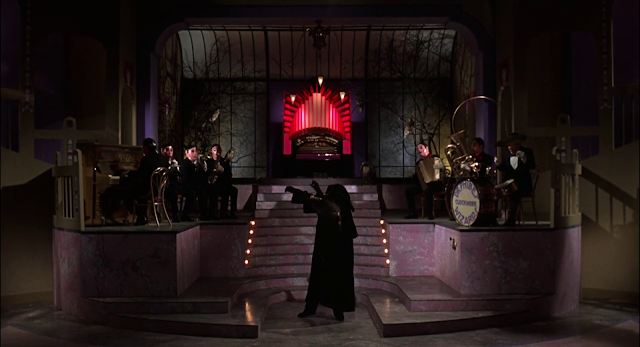

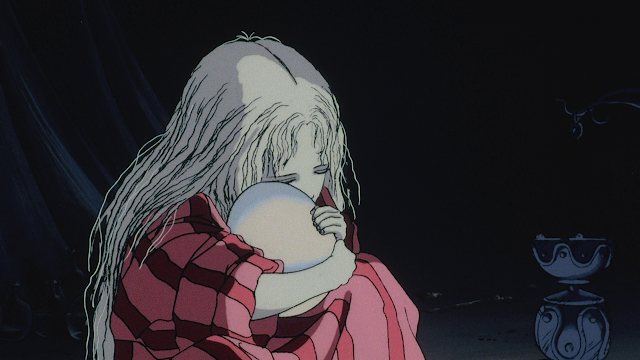

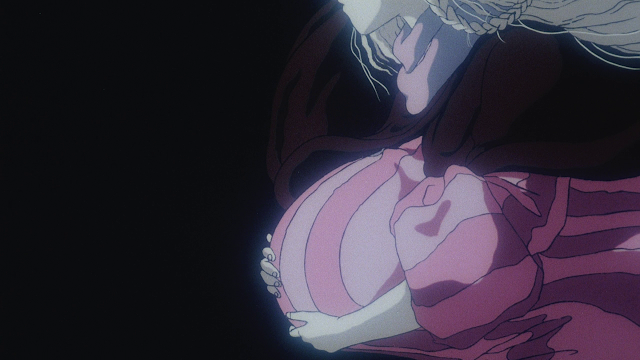

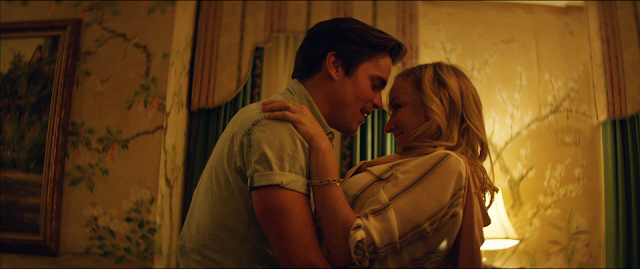

The romantic angle often gets bogged down by the male character's problem life at home or his persistent blandness, but Amirpour manages to wrangle their story into something cohesive by the end. The meet-cute (meet-fang?) of their first time spent together is very sweet. Dracula finds someone he can relate to, and she finds a boy she doesn't want to kill...yet. They end up heading back to her place on a skateboard she just stole from a boy who consistently behaved badly in the neighbourhood. They don't have a ton in common, but they enjoy each other's silence and there is a level of comfort between the two. The grandest scene of the entire movie comes just a little bit later with the two of them back at her apartment. The vampire stands to the far right, a disco ball twirls in the room sprinkling light all over, and as the boy approaches her as music washes in and out in ever quiet waves she stares into his eyes, and then his throat. We know that she is a vampire so the precedence of this scene has viewers asking Will she kill him or kiss him? She eventually puts her head on his shoulder, and it's the finest scene in the entire picture. A moment where Amirpour's rough, but often interesting vision coalesces into a purely perfect moment.

Amirpour's horror picture isn't the groundbreaking feminist picture it's title implies, but it doesn't need to be. There are some ideas about patriarchal violence, and images that back up the strength of a female figure daring to push back at this, but this is mostly a gorgeous amalgamation of ideas she struggles to tie together. There's enough here though to warrant further explorations into the future work of Amirpour and plenty talent on display to be excited about what her next movies may look like.

The first thing one would notice about this movie is the stylization of the image. Night time cinematography gives way to dusty digital black and white in what has to be one of the first usages of B&W digital to grand effect. Lights feel hazey and street lamps decorate streets row upon row as far as the eye can see creating a sense of almost suburban trappings meets the old west. Amirpour's intentions of making the picture feel like a western aren't lost on her sensibilities to reach back to cinema of the past to give weight to some of her ideas. The urban streets traveled by no one except a cloaked girl aren't entirely separate from wanderers of the old west like Clint Eastwood in High Plains Drifter. The old drunk trope is replaced by an elderly relative stricken by grief and hooked on heroin. These are tropes certainly, but Amirpour works well within them, and her knowledge of cinema past increases the effectiveness of her concrete wasteland. Aside from those western locales there is an intense interest in interior design with each room signifying the attitudes of specific characters. Her first victim lives a chic lifestyle that is coded by tacky animal print everywhere. The Vampire lives in a basement with paintings of Madonna on her wall, and the rest of her room seems to be corroding around her. The insertion of character dynamics via interior design and cinematography that doesn't feel watery like other BW Digital work (Frances Ha) are some of the more impressive feats here.

Scenes of violence tend to forgo the western and dip back into horror, and occasionally feminist horror. The black and white of Abel Ferrara's The Addiction is handled with much more chaotic-frenzied-brutality than this picture, but The Addiction came to mind specifically in feeding sequences while I was watching this. Lily Taylor's vampire intellectual and Shelia Vand's vampire, misandrist, queen both have no predisposition towards softness, and their killings often revel in the sensuality of the feast. Vand's vampire specifically only attacks men, and I think that codes this with some feminist text, even though the picture refuses to analyze these things much deeper than her only killing males (though the way she does kill the first man in this picture is reminiscent of Teeth). It can be read that she is cleansing the streets, but that's only the case until she falls for a boy dressed as dracula.

The romantic angle often gets bogged down by the male character's problem life at home or his persistent blandness, but Amirpour manages to wrangle their story into something cohesive by the end. The meet-cute (meet-fang?) of their first time spent together is very sweet. Dracula finds someone he can relate to, and she finds a boy she doesn't want to kill...yet. They end up heading back to her place on a skateboard she just stole from a boy who consistently behaved badly in the neighbourhood. They don't have a ton in common, but they enjoy each other's silence and there is a level of comfort between the two. The grandest scene of the entire movie comes just a little bit later with the two of them back at her apartment. The vampire stands to the far right, a disco ball twirls in the room sprinkling light all over, and as the boy approaches her as music washes in and out in ever quiet waves she stares into his eyes, and then his throat. We know that she is a vampire so the precedence of this scene has viewers asking Will she kill him or kiss him? She eventually puts her head on his shoulder, and it's the finest scene in the entire picture. A moment where Amirpour's rough, but often interesting vision coalesces into a purely perfect moment.

Amirpour's horror picture isn't the groundbreaking feminist picture it's title implies, but it doesn't need to be. There are some ideas about patriarchal violence, and images that back up the strength of a female figure daring to push back at this, but this is mostly a gorgeous amalgamation of ideas she struggles to tie together. There's enough here though to warrant further explorations into the future work of Amirpour and plenty talent on display to be excited about what her next movies may look like.